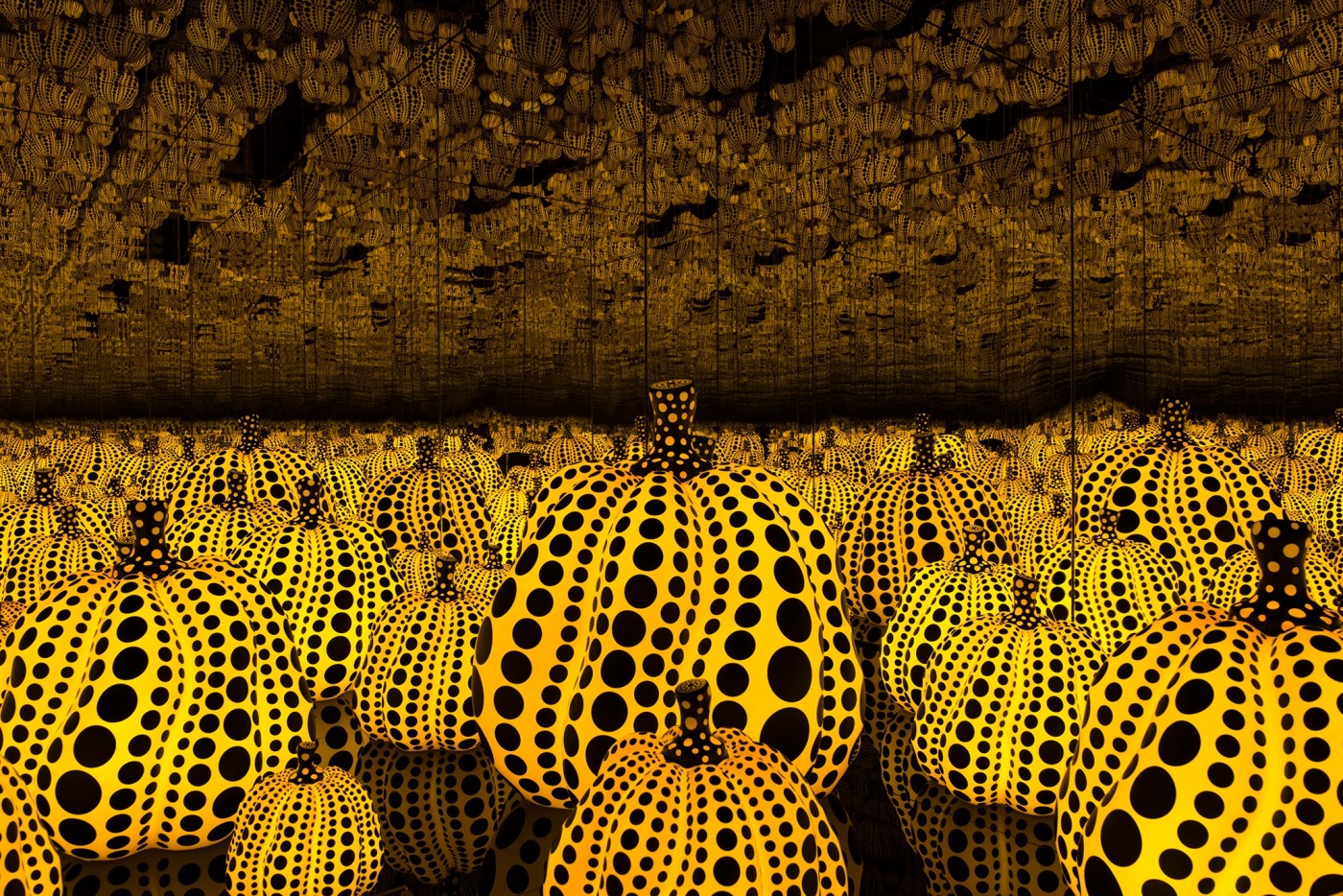

Often referred to as the ‘princess of polkadots,’ Yayoi Kusama is a painter, sculptor, performer, and installation artist. She utilizes entire spaces to reflect on experiences of her past and create a Kusama world. Kusama’s talent and brilliance has largely gone unnoticed her career, that was until social media turned her art into a perfect photo opportunity. In the past five years, over five million visitors have waited in line to see Kusama’s work. She is an 89-year-old Japanese artist who has major shows in Mexico City, Rio, Seoul, Taiwan, Chile, Europe, and the U.S. Kusama’s installations of ever immersive ‘infinity mirror rooms’ attract a vibrant crowd of people hoping to capture a piece of the magic.

The rooms which include mirrors, coloured lights, painted pumpkins, and lots of polka dots that reflect for forever. Museums have recently began looking at exploring the ideas of exhibitions for upload-able social media experiences. Kusama has been developing her spacey wonderlands since 1966 and has mastered it. These exhibitions are coinciding with the release of of the film Kusama: Infinity. The director, Heather Lenz, had pitched the biography since 2001, but was told it was ‘too artsy,’ Kusama had ‘no name recognition,’ and ‘no one wants to watch a movie about a woman artist.’ Although a lot of people have seen her work on Instagram, many are shocked to hear what she had to go through to achieve success, but it makes her more relatable. Many are unaware of the fact that she has voluntarily lived in a psychiatric hospital for 41 years. Kusama’s struggle to escape obscurity has less to do with her art and more to do with her identity and past, making her rise to popularity even more impressive and inspiring.

The art world historically seems to be dominated by men. It seems that the reputation of reflection and progressiveness of modern art seems to mask injustice and unfairness. Artists and art critics continually overlook the talent and ability of female artists, especially female artists of colour. One example stands out for me, the story of Helen Frankenthaler. The latter, Frankenthaler, is an abstract expressionist painter. Frankenthaler, a painter from the 50’s came from a period where the art world’s next big star were exclusively men. One emergent painter included Jackson Pollock. A large part of this has to do with Clement Greenberg, who became the most influential art critic of the 20th century. In New York’s small art circle, Greenberg became an important eye in the scene, while remaining obscure to the general public. While Greenberg was largely a rookie, he was respected by painters for sharing their attention to detail, even though he never painted himself and was only a critic. Greenberg had an abrasive, hyper-masculine view of the art world that shifted the attention from Paris to New York, landing a lot of attention on Pollock, the cowboy painter of the midwest. Greenberg is responsible for shedding light on these masculine and “American” painters of this era. His essays described Pollocks paintings aggressively, explaining that he “pulverized” the canvas and made “violent repentance” as his style changed. Pollock by no means is untalented or undeserving of the attention. However, the narrative of masculine, American, aggressive painting laid out by Greenberg and critics to follow, left female and immigrant artists on the sidelines, due ti the fact that they didn’t fit the vision as tightly. Helen Frankenthaler didn’t splash paint like Pollock, but she shared in the big canvas expressionism by soaking and staining. Mountains and Sea, 1952 is haunting and beautiful.

Kusama saw her first pumpkin with her grandfather, and when she went to pick it up, it began speaking to her. She went home and painted the pumpkin at age 11, winning a prize for her work. Eighty years later, her largest silver pumpkin sculpture would sell for $500 000. When Kusama was 13, she was conscripted to work in a factory that produced parachute fabric as World War II developed. In the evenings, she would paint intricate flowers over and over again with watercolour, reportedly producing 70 a day. Both her work at the time and her art today is heavily influenced by the trauma she experienced as a child, which goes hand in hand with a society shaped by the second world war and expectations that were restrictive to the role of women. The expectation at the time for a young Japanese woman was an arranged marriage and kids, not much else. Kusama boldly decided to leave Japan for New York.

Kusama encountered the work of Georgia O’Keeffe in her hometown; she found O’Keeffe’s New Mexico address and wrote asking for advice on making her way into the New York art world. Their relationship developed into a mentorship of sorts. O’Keeffe replied,

In this country an artist has a hard time making a living. You will just have to find your way as best you can.

At age 27, Kusama arrived in New York in 1958, with only a few hundred dollars, 60 silk kimonos, and drawings. Her plan was to survive either with her art or by selling the traditional Japanese attire. She survived by making soup out of fish heads and trailing her work around the city. Kusama recalled in her autobiography,

I carried a canvas taller than myself 40 blocks through the streets of Manhattan to submit it for consideration at the Whitney Annual. My painting was not selected and I had to carry it 40 blocks back again. The wind was blowing hard that day and more than once it seemed as if the canvas would sail up into the air, taking me with it. When I got home I was so exhausted I slept like the dead for two days.

Kusama’s breakthrough began with her Infinity Net paintings, which emerged from an earlier set of watercolours in response to watching the waves on the surface of the sea as she flew for the first time from Tokyo. The nets sere painted from a repetitive single gesture of impasto in little loops, the longest fo which measuring thirty feet. The first ones she sold to fellow artists Frank Stella and Donald Judd in 1962 for $75. In 2014, one of these canvases set a record for a living female artists, selling for $7.1 million. The infinity net began Kusama’s start as an environmental artist. When she would work on these nets, she would carry the painting over the studio floor, transforming the space into a large installation, creating the groundwork for her immersive installations that she is known for today.

.jpg)

In 1963, Kusama began making chairs and other objects covered with white painted phallic forms made of stuffed fabric. The centre of this series was Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show, which featured a rescued rowing boat, presented in a box-like space, the walls, ceiling, and floor papered with 999 silk-screen images of the phallic boat. Kusama treated the soft sculpture , phallic-oriented installations like her own aversion therapy.

Kusama explained,

I began making penises in order to heal my feelings of disgust toward sex. My fear was of the hide-in-the-closet-trembling variety. I was taught sex was dirty, shameful, something to be hidden. Complicating things even more was all the talk about ‘good families’ and ‘arranged marriage’ and the absolute opposition to romantic love… Also, I happened to witness the sex act when I was a toddler and the fear that entered through my eye had ballooned inside me.

It was around thus time the Kusama found Joseph Cornell, the reclusive genius of outsider art, a maker of boxes of found objects, and a man who always lived with his mother. Cornell was the ideal man for Kusama; he quickly became obsessed, sending her a dozen poems a day and never hanging up from the phone so he was there when she picked it up to dial. This was her only known romantic relationship, though Kusama explained,

he didn’t like sex, and I didn’t like sex so we didn’t have sex.

It was in the 60’s that Kusama began experimentation with creating an infinite illusion with mirrors. She is famously photographed in a boxed and mirrored room filled with stuffed phalluses marked with her iconic red polka-dots.

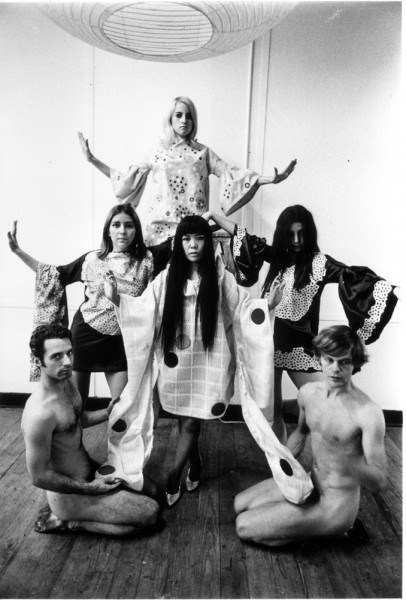

In the summer of 1967, which is also referred to as the summer of love, Kusama desired to position herself as a high priestess of flower power. She would stage ‘Anatomic Explosion happenings’ where she painted nude men and women with dots, and placed them around New York, including on the steps of the Statue of Liberty and famously opposite the Stock Exchange to protest that influence of American capitalism in the continuance of the Vietnam war. Jeanette Hart, one of Kusama’s performers remembers,

I was thinking ‘portrait.’ It never occurred to me that it meant literally ‘paint me.’

While Kusama’s explosive and infinitely spectacular career as a young artist in New York is appreciated more today, at the time, Kusama seemed to be written out of pop art history. In the 1960s, Kusama shared equal notoriety with Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg, two prominent figures in the pop art scene. It seemed that Kusama was aware of this ignorance towards her as pop art grew, as she has long claimed that her original ideas were appropriated and made commercially successful by men who would pass it off as their own. There is more basis to this claim when it’s recognized that her soft sculpture appears to have been adopted by Oldenburg and her repetitive wallpaper prints by Warhol. She struggled with the fact that these men found fame with the ideas she called her own.

While the potency of these allegations is still fairly unknown, it can be said that Kusama’s beliefs and identity, put her behind her particularly male counterparts. In November of 1968, half of a century ahead of its time, Kusama staged New York’s first ‘homosexual wedding,’ for which she created a ‘wedding dress for two’ and conducted the ceremony. Kusama would create spotted clothes from a boutique with holes to reveal breasts and buttocks, which cemented her notoriety in America, but also in the deeply conservative Japan. However, she was treated as the scandalous exile as her career progressed. Media interest quickly shifted from serious critical attention to superficial exposes, creating a connotation around her name that associated her with excess and orgies.

Kusama was deeply affected by the death of Jospeh Cornell in 1972 and her own father in 1974. As she grew into a New York outcast, Kusama returned to Japan to try and start over again. She rented an apartment in Tokyo that faced a large cemetery, and likely inspired by her former partner, began working on surreal collages. However, her hallucinations and panic attacks returned from her adolescence with full force, leading her to be hospitalized several times. Her work highlighted her isolation and feelings of entrapment. In March of 1977, Kusama admitted herself to a psychiatric hospital.

For Kusama, her permanent stay in a psychiatric hospital represented a new start, where she has been able to manage her struggle with mental illness and direct it creatively. The hospital offered art therapy courses, which she signed up for and continues to use today. Kusama sleeps at the hospital each night and works in her studio across the road six days a week, She eats sushi, she makes her own clothes, and she has little interest in the wealth that has come to her late in life. Kusama has a small team that looks after her popular work around the world. Her work is present in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Florida, London, Lille, Naoshima, Tokyo, and Canberra. Kusama’s recent art continues to explore infinity and dotted obliteration, tying into her childhood with pumpkin and phallic motifs.

Scott Wright, one of Kusama’s assistants, has watched her rise over the past 25 years.

We had an Infinity Mirror Room at the first Victoria Miro show at Cork Street [in 1998] and practically no one came. The last show we had 80,000 visitors.

One reason for this success, Wright believes, is the need for art establishments to make amends for not recognizing her to the same degree as her male counterparts. Kusama is undoubtedly a prominent figure in pop art and minimalist, but until recently, she hasn’t been recognized as one.

She was doubly an outsider – a woman, and a Japanese woman. She just wasn’t recognized in the way the white male artists were. In retrospect it is clear she was a very important figure both in minimalism and in pop art. Her work provided a link between the two, which was unique.

Kusama has a profound universal appeal. Even early shows people of all backgrounds were entranced in a sense of wonder. She has achieved serious critical acclaim and immense popularity, which rarely goes hand in hand. Kusama’s work, while remaining inherently personal, has the capacity for profound popularity and commercialization, due in part to its consistency and uniqueness. This was extremely present when Kusama collaborated with Louis Vuitton, creating perhaps the biggest art and fashion collaboration ever.

Wright explained that Kusama,

paints on a flat surface and sits in a chair, but she will get up and move around. She is not much interested in hearing art world gossip, she wants to talk about her own work. She doesn’t talk about [success] so much, but she says she always wanted Kusama to be everywhere, so she appreciates that.

The internet has helped recognize Kusama’s bursting talent. Although she doesn’t do interviews, she once wrote,

I am determined to create Kusama world, which no one has ever done and trodden into.

Kusama continues to develop her ‘Kusama world,’ even in her old age. She long ago decided that she would express her thoughts through art until she died, even if no one ever saw it. Living in a psychiatric hospital has helped her focus her expression tremendously, painting, drawing, and writing from morning until dinner. Her unique take on narcissism and exploration with mirrors came at an appropriate time. One visitor for All the Eternal Love I have for the Pumpkins stumbled and shattered a pumpkin trying to capture the perfect selfie.

Kusama always has and continues to be a trailblazer in the art world. While the context of her identity as a Japanese woman was inherently restrictive to her success as a young artist, her focus on aesthetics and consistency has cemented her position into a well loved artist. Her experience as an artist in New York is reminiscent of the women, particularly women of colour, who continue to be ignored both in the art world and other industries. However, Kusama’s work was much louder than the bias she had to fight through, and her work continues to provide a symbol of perseverance and self-survival, which Kusama continues to explore today as she busily works in he studio. This symbolism becomes exponentially more potent as her art continues to focus its attention to the audiences own experience within it, at times, even allowing them to change it and make the environment uniquely theirs. The beauty of Kusama is that her art, while exactly her own, is meant to be shared, bridging the gap between artist and audience, in a powerful linkage.

Sources-

Photos-