Basic economic theory as we know it today is based heavily on a series of generalizations about how people act. That looks like describing the movement of prices in response to changes in supply. It also looks like looking at how government spending would affect the unemployment rate.

Today, the models economists use to predict behaviour are, in most cases, mathematically complex and highly precise. However, over the past few decades, studies have repeatedly shown that they often fall apart in the real world.

This is the intersection between economics and psychology: behavioural economics.

The thesis of this field is that real people do not behave with perfect rationality and optimization. We’ll call this perfectly rational economic agent Homo economicus—or “econs” for short (as Richard Thaler, a leading behavioural economist, does in his book Misbehaving).

Humans are fallible to psychological tricks and their own biases. Econs are not.

An Exploration of Human Behaviour

Sometimes, humans behave in at-first inexplicable ways. Below are a few well-known examples that behavioural economics has explored over the past few decades.

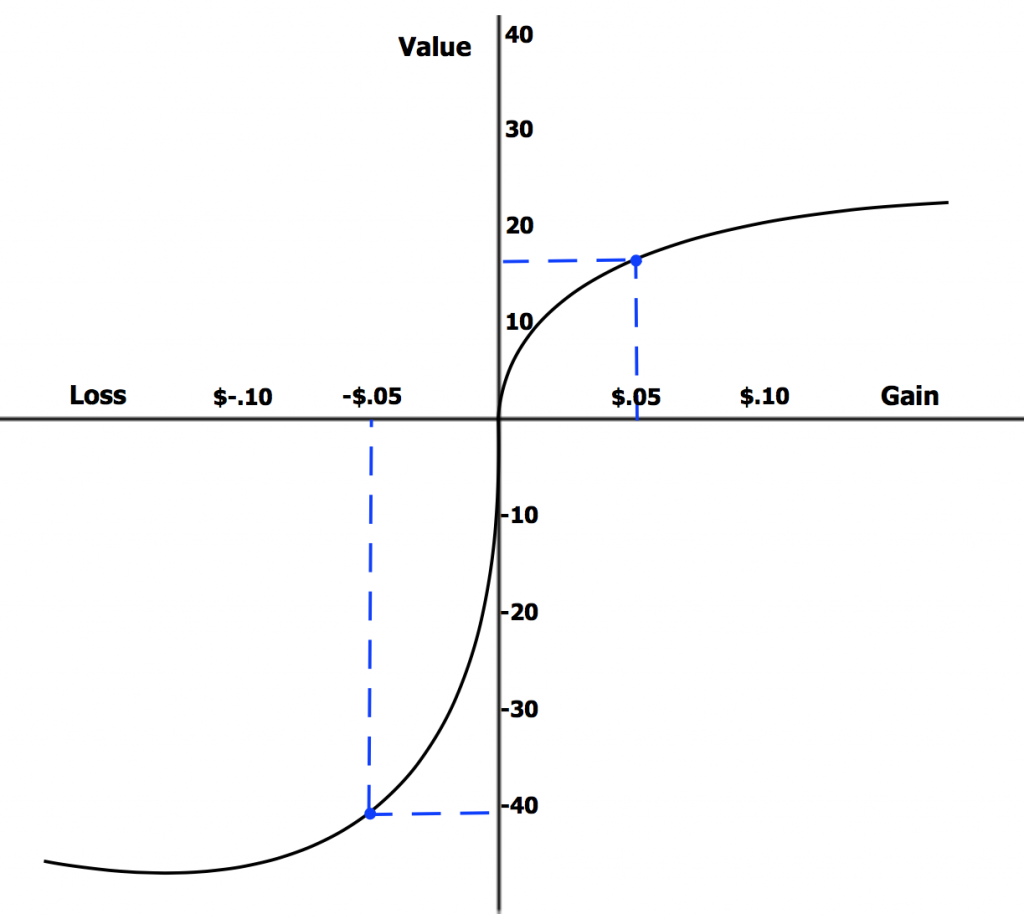

- The Endowment Effect. People value things that they already own more than things that could become theirs. In one classic study, participants who were given a mug would only accept an offer to sell the mug that was roughly twice what they would pay for it themselves. The idea here is that individuals’ willingness to pay is generally lower than what people would accept to sell the same item once they already have it. One explanation of this is the idea of loss aversion—that although people like gains, they hate losses disproportionately more.

A loss of $0.05 may be perceived as a greater loss of value than a gain of $0.05. - Just-Noticeable Difference. The human mind is used to thinking in terms of proportions. And when talking about prices, for instance, certain absolute differences don’t mean much if they are proportionally unnoticeable. Consider this thought experiment: how far would you go to get a $5 discount on a $10 item? How about a $5 discount on a $1000 item?

- The Sunk Cost Fallacy. Here, the idea is that an econ would always make a decision based on present opportunity costs, not how much has already been “sunk” into an endeavour. For example, continuing to buy, say, a Costco or Amazon Prime membership, even though it may not be worth it, is illogical. However, due to the principle of payment depreciation, people often continue the membership so that they can get their worth out of their previous sunk costs.

Heuristics

These examples, and numerous others, demonstrate a principle that pervades psychological behaviour: the idea of a heuristic.

Heuristics are rules-of-thumb for making decisions. When humans choose to buy something, we aren’t meticulously calculating the expected utility we would gain and comparing it to the cost. We frequently make split-second decisions based on personal knowledge and past experiences, which may not be very precise. These are heuristics.

The extent of our own knowledge and experience limits the usefulness—and optimality—of heuristic-based decisions.

For example, goods and services we don’t buy very often—weddings, for example—are often very difficult to pinpoint in terms of value vs. price. It’s very difficult for us to judge whether something is too expensive or a good deal if we aren’t already familiar with it.

Moving forward, behavioural economics continues to expand. To better understand economic behaviour on a large scale, economists increasingly recognize the importance of psychology in individual decisions.

After all, humans are not econs, and we can’t expect ourselves to act like them either.