The few wandering elephants that roam Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park are the lone survivors of their formerly large community, all bearing the indelible markings of the civil war that gripped the country for 15 years: Many are tuskless. The conflict, as well as years of prior poaching, killed off about 90% of these animals in order to satisfy a quota of ivory to finance weapons or for meat to feed the militia.

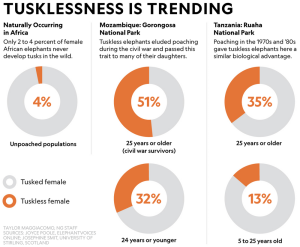

From 1977 to 1992, both sides in the war hunted the elephant populations for their prized ivory tusks leading to their eventual plummet in numbers. This same activity very well may have set off an evolutionary response in the species that favored tuskless elephants as the species numbers began to recover. Nevertheless, despite the fact that lacking these tusks may have saved some from being poached, the genetic mutation responsible for eliminating the tusks is lethal in male elephants. As elephant numbers dropped from the thousands to mere triple digits, with around only 200 surviving in the early 2000s, many female elephants survived the poaching but were overlooked as they already were naturally tuskless. These elephants were then able to pass on their gene of tusklessness down to their offspring after the war ended. A study by Princeton University has shown that the proportion of tuskless females rose from 19 to 51 percent during the conflict, and statistical analysis indicated this was extremely unlikely to have occurred in the absence of selective pressure. This loss of tusks has been documented in many other places as well; Sri Lanka has less than 5 percent of their male Asian elephants having tusks. Details of the study were published in the research journal Science.

From 1977 to 1992, both sides in the war hunted the elephant populations for their prized ivory tusks leading to their eventual plummet in numbers. This same activity very well may have set off an evolutionary response in the species that favored tuskless elephants as the species numbers began to recover. Nevertheless, despite the fact that lacking these tusks may have saved some from being poached, the genetic mutation responsible for eliminating the tusks is lethal in male elephants. As elephant numbers dropped from the thousands to mere triple digits, with around only 200 surviving in the early 2000s, many female elephants survived the poaching but were overlooked as they already were naturally tuskless. These elephants were then able to pass on their gene of tusklessness down to their offspring after the war ended. A study by Princeton University has shown that the proportion of tuskless females rose from 19 to 51 percent during the conflict, and statistical analysis indicated this was extremely unlikely to have occurred in the absence of selective pressure. This loss of tusks has been documented in many other places as well; Sri Lanka has less than 5 percent of their male Asian elephants having tusks. Details of the study were published in the research journal Science.

Scientists began collecting data on the elephants at Gorongosa National Park to research this amplified natural selection towards tuskless elephants, and it was then that they realized that elephants with no incisors were usually female. The park has never seen a tuskless male, suggesting the trait related to tusklessness is not only sex-linked but it will lead to the death of any male elephants that the gene is passed down to.

Using 11 females without tusks and 7 females with tusks, a research team was able to identify the two mutations involved. One of the said mutations is most likely to be in a gene X chromosome called AMELX, which plays a part in tooth formation. This same mutation appears to affect other, crucial genes nearby. Since females would have two copies of the X chromosome, if one copy is not mutated, the genes will still carry their function normally and the elephant will be healthy. However, since males only have one X chromosome, the mutation will be deadly to any males that inherit it. “When mothers pass it on, we think the sons likely die early in development, a miscarriage,” says study co-author Brian Arnold, a Princeton evolutionary biologist, to the Associated Press.

It is still possible that further genetic changes could occur to compensate for the lethality and males would eventually lose their tusks too, but for now, this does not appear to be happening. However, even the loss of tusks in females can have all sorts of consequences for the environment and the species at large. The main researcher at Princeton who was in charge of the study, Shane Campbell-Staton, stated that, “Tusks are basically a Swiss army knife for African elephants.” They use them to strip the bark off trees, to dig holes for underground water or minerals, and so on, says Campbell-Staton, so the loss of tusks may spare females from poachers, but make it harder for them to survive in other ways. On top of that, other animals in the ecosystem still rely on these tusked animals to survive such as using the same holes dug by the tusks to get water for themselves. As Campbell-Staton best said in his report, “there are all these cascading consequences that can result from our actions that are quite surprising.”