On March 14, 1979, Judy Chicago’s art instillation, “The Dinner Party,” was opened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. That instillation pushed feminist art to the limelight, changing the lives of women, and forever defining Chicago as a legend. Now, “The Dinner Party” is permanently installed in the Brooklyn Museum, but the life of Chicago’s art has experienced intense criticism rooted in patriarchal discrimination and sexism. In the recent documentary, “Feminists: What Were They Thinking,” women photographed by Cynthia MacAdams, a photographer who was recognizing a definitive change in women and began photographing them in the 70’s, explained there relationship to feminism. Chicago emerged as a clear voice for women, and an important example of the dire necessity for true anti-sexism in art.

…I got sick to death of trying to “act like a man,” “paint like a man,” you know, not be myself as a woman… of course, [feminist literature was] speaking to everything I’m feeling… I was getting really pissed off by being told that I couldn’t be a women and an artist too. I was watching the men get moved along on the choo-choo train of success and everything. Every single instance of moving forward… I wouldn’t sell anything. You couldn’t really talk at that time about sexism, but I decided to start speaking out.

Judith Sylvia Cohen was born on July 20, 1939, began drawing at age three, and was immediately recognized for her talent by her preschool teacher. Her mom enrolled her in Saturday art classes at the Chicago Art Institute. Five days before her 14th birthday, Chicago’s father, Arthur Cohen, died of complications during surgery. In her interview for the documentary “Feminists: What Were They Thinking,” Chicago explains that,

For a women of my generation I had a very unusual experience, which was I was really fathered.

Arthur’s death was devastating for Chicago, and she took refuge in her art.

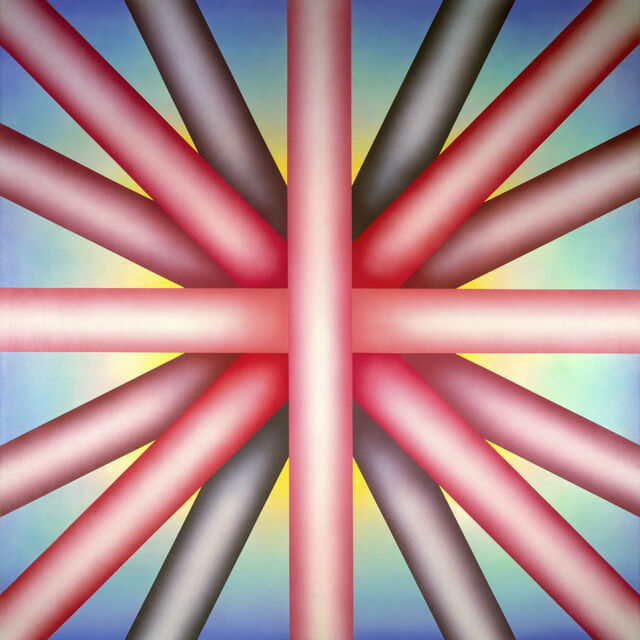

Chicago enrolled at UCLA, where she majored in art and minored in humanities. Here, her professor of Intellectual History of Europe stated that women have made no contributions to history, inspiring Chicago to prove him wrong, and ultimately, leading to “The Dinner Party.” Tragedy struck again, when before the age of 24, in 1963, she was widowed after her husband, Jerry Gerowitz, died in an automobile accident. Again, Chicago found solace in her art. After earning her master’s degree in sculpting and painting from UCLA, Chicago enrolled as the only women in a 250 people auto-body class to experiment with spray painting. The year of 1965 began with Chicago’s minimalist work. “Rainbow Pickett” was featured in New York’s Jewish Museum for the “Primary Structures” show. Chicago was one of the few women being recognized for their minimalist work at the showing, and “Rainbow Pickett” was featured in the Time Magazine’s review.

Chicago also attended a boating school in Long Beach to learn how to work with fibreglass. There, she created “10 Part Cylinder” in 1967 for the “Sculptures of the Sixties” exhibition for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. She was one of only five women included in the exhibition. From 1968 to 1974, Chicago continued to experiment with different mediums. Working with flares and fireworks, Chicago enlisted her friends to travel across Southern California and release coloured smoke in an attempt to feminize the surrounding environment in a project called “Atmospheres.”

During this time, Judy Chicago legally changed her name from Gerowitz to Chicago. She officially announced this in an ad for her first solo show at Cal State Fullerton.

Judy Gerowitz hereby divests herself of all names imposed upon her through male social dominance and freely chooses her own name: Judy Chicago.

In the spring of 1970, Chicago joined the faculty at Fresno State College to teach a women’s only art program. A radical idea at the time, Chicago encouraged students to express their experience as women through their art, involving the use of traditionally male dominated tools and mediums. In 1971, Chicago wrote,

I want to begin to establish regular contact with the growth of the first Feminist Art ever attempted.

She renamed the course “Feminist Art Program,” eventually leading to the establishment of “Womanhouse.”

One of Chicago’s most prominent works of feminist art was the establishment of “Womanhouse.” From January 30 to February 28, 1972, along with Miriam Schapiro, a co-founder of Cal State’s “Feminist Art Program,” Chicago renovated house 553 Mariposa Avenue in Hollywood with 21 women. For three months, the women repaired the house, along with adding their own revolutionary installations. “Womanhouse” was the first openly female centred art instillation, attracting 10 000 people in the month it was open.

The Works of Womanhouse:

In 1973, after “Womanhouse,” America’s sexual revolution was in full swing. Chicago delved into her art exploring the female expression with works like “Through the Flower,” “Heaven is for White Men Only,” and “Let It All Hang Out.” She also began writing “Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Female Artist.”

As a part of the “Sculpture in the City” project in Oakland, Chicago created “A Butterfly for Oakland,” made out of 200 sunset coloured road flares. Burning for 17 minutes, it began the year of the early beginnings of “The Dinner Party” (1974), one of the most iconic and unfortunately controversial pieces of feminist, contemporary art.

The Dinner Party:

“The Diner Party” is a triangle shaped table with 39 place settings, evoking the acute feeling of a distinguished gathering. Each plate contains a glowing centre with wings, petals, and flames, expressing variations of the vulva. With each place setting, is a runner, embroidered with elaborate designs and names of woman of accomplishment who are unfortunately, mostly unfamiliar. There are 999 names of heroic women, many of which have been ignored in history lessons. “The Dinner Party” opened on March 14, 1979 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. It was an immediate sensation, pointing towards Chicago’s skillful, traditional work, along with her theatrical and inherently feminist style. The instillation is now permanently installed in the Brooklyn Museum. Chicago spent years of creating and organizing, utilizing 5 years and a 400 person volunteer force to complete the project. Her intention for the project was to rededicate the history of Western civilization to the women who are consistently left out. The intention of the size the instillation was to making something so large, that the history of women could never be erased.

From the beginning, you know, I was determined — it needed to be permanently housed, because if it hadn’t been, it would have simply reiterated the story of erasure it recounts. It just — I had no idea it was going to take this long.

In the first three months of the original San Francisco showing, 100 000 people attended. Chicago received praise from women who said she changed their lives with the installation. However, colleagues and politicians claimed it was a crude piece of political rhetoric. The Los Angeles Times called it,

a lumbering mishmash of sleaze and cheese.

Shocked, Chicago felt rejected and retreated to her studio, $30 000 in debt. “The Dinner Party” was dismantled and boxed up. For the next two decades, the installation was ignored by art institutions, with the exception of the Brooklyn Museum, which showcased it in 1980, prompting more ridicule. The project coordinator, Diane Gelon, firmly believed in the project, and through alternative showings, “The Dinner Party” was reinstated into art history, along with the revolutionary women showcased through the piece. In 2002, it was reacquired by the Brooklyn Museum.

Call it what you will: kitsch, pornography, artifact, feminist propaganda or a major work of 20th-century art… It doesn’t make much difference. ‘The Dinner Party’ … is important.

The party is both a deep dive into history, from a true matriarchal standpoint, but also a piece that showed Chicago’s evolution. A writer for The New York Times believes that if the installation was created in 2018,

It would have penetrated the culture so deeply that it would have been impossible to reject.

Yet, it was still able to accomplish that. The work is humorous, frank, and sincere. It asks: what would the world look like if women held power? A question still being asked today. Chicago elegantly described the value of her work,

Look, you know, before I get interested in somebody, they have to have a long, sustained career. Because that’s what real art grows out of. Not the ‘make-it’ dream, not bursts of youthful ingenuity, not critical acclaim — just continuing, no matter the circumstances, to make art. ‘That,’

she said,

is what I admire.

After “The Dinner Party,” Chicago continued her career as a feminist artist, releasing “Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist” in 1975, she returned to teaching, and continued to create. In 2010, Chicago worked with art historian Frances Borzello to create “Face to Face: Frida Kahlo,” a handpicked collection of Kahlo’s work that speaks to the female experience. The work of Chicago continued to be appreciated and showed, giving a voice to a constantly oppressed female voice, and giving a voice to the resilience of Chicago herself. To celebrate her 75th birthday, Chicago explored her early feminist imagery and created “A Butterfly for Brooklyn,” in 2014.

From 2007 to 2013, Chicago worked on the diverse series “Heads Up.” It includes watercolours, sketches, two-dimensional painted glass, and three-dimensional cast glass and ceramic heads.

Judy Chicago’s 1983 “Earth Birth” from her “Birth Project,” was featured in Salon 94’s Frieze New York booth in 2016.

Most recently, in one of the most landmark years for feminism, Judy Chicago was named Time’s 100 Most Influential People in 2018.

It is ironic that after all these years, where I was once critiqued I am now being lauded. My goal has been to make a contribution to a more equitable world through art and I am honoured and thrilled that my work is being recognized now by TIME. I am grateful to all those who have supported me on this long and challenging journey.

Even since her early works, Chicago undeniably made her mark as a feminist, talented artist, and an earnest voice in modern art, creating undeniable strides towards equality both in art, and in North American society as a whole. She is and will be the Godmother of feminist art.

Sources-

Feminists: What Were They Thinking?

Images-

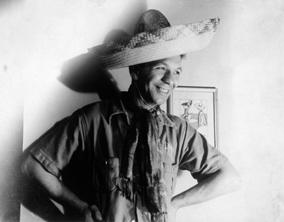

Judy Chicago making The Dinner Party

A Note from the Author:

I was first introduced to Judy Chicago in the documentary “Feminists: What Were They Thinking?” I was immediately struck by her unconventional fashion and attention-grabbing energy. After hearing a little bit about her experience with “The Dinner Party,” I researched her more. In my personal opinion, she is the most creative, relevant, diverse, and earnest artist of the more modern day. I found her assertive and forward art completely infatuating, and her work is still as relevant and necessary as it ever was. I strongly believe it will survive the test of time. With 2018’s strong continuation of the #MeToo movement, the internet asked the same questions that Judy Chicago did decade’s ago: what would the world look like if women were empowered? Chicago’s and the world’s response to the question is utter beauty. Chicago’s ability to go from minimalism, to blowing up fireworks, to mixing traditional art with modern rhetoric is unparalleled and is the magic, survival, and resilience that is Judy Chicago. I’m extremely excited to see what Judy Chicago does this year. Even after decades of art, Chicago is continuing to work and bring attention to some of her old pieces that got lost when she was pushed to the sidelines due to the femininity of her work. Above all, what I admire most about Judy Chicago is her unapologetic personality and experience that clearly shines through in everything she does. I think this image portrays that directness and uniqueness the best… to me, she immediately stands out, and for that audacity I’m extremely thankful.