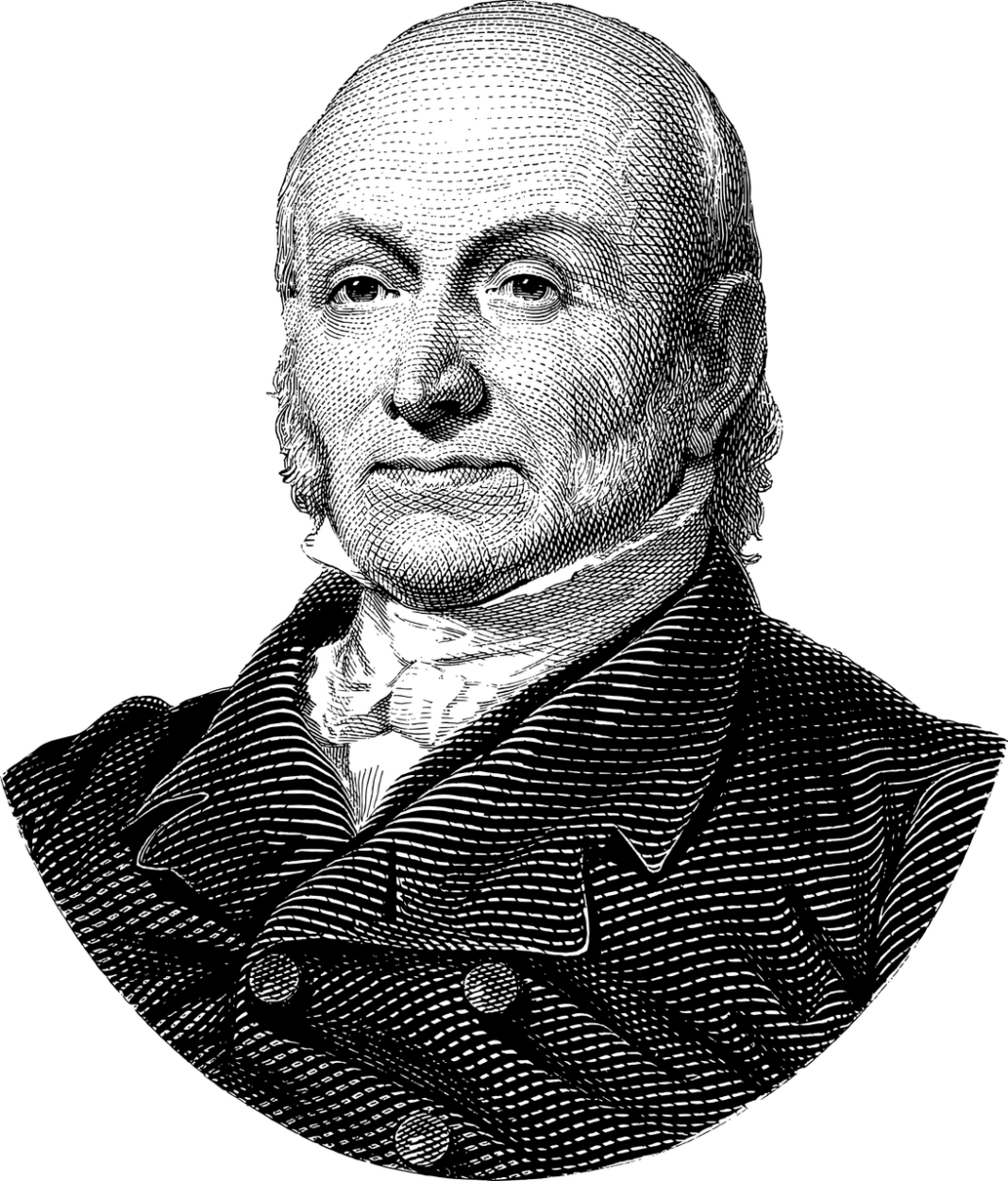

For someone who remains as relatively unknown as John Quincy Adams, his impact on how governments across the world run today is enduring. This article serves as a part two for an article published several months ago about the life of Frederick Douglas, and serves as an introspect into another influential historical mind.

Early Life

Born the son of influential lawyer, diplomat, and future-President John Adams, on July 11, 1767, Adams spent the majority of his childhood in Massachusetts, under the care of his mother, with his father off serving as a leading figure of the American Revolution and negotiating with foreign powers on behalf of the young republic.

However, Adams would not spend much time in Massachusetts, as when he was just 10, his father was commissioned by Congress to serve as the Ambassador to France. Adams would accompany his father on his journey, spending his time in Europe learning to speak French, Greek, and Latin, as well as taking courses at several universities. Three years later, at age 13, he was sent on his own to serve as secretary for the U.S. Ambassador to Russia, an opportunity he again used to learn new languages and about foreign cultures. In 1785, he returned to America alone, with his father now serving as Ambassador to Great Britain.

Within two years of his return, Adams graduated from Harvard University and began studying to become a lawyer. While studying, his father would be elected as the first Vice President, running on a ticket with George Washington, who would concurrently be elected as the first President.

Early Career

In 1794, on the advice of his father, Washington appointed Adams to the position of Ambassador to the Netherlands. While back in Europe, he worked to secure essential loans for the United States, which helped the new nation stay afloat in its early years and helped enact Alexander Hamilton’s plan to take on foreign debt and build credit with foreign powers. In 1797, upon his father’s ascension to the Presidency, he was appointed as Ambassador to Prussia, responsible for negotiating new trade deals with Prussia and Sweden on behalf of the United States. During this time, Adams was crucial in helping to build foreign relations for the U.S.

In 1800, after his father lost his re-election bid to Thomas Jefferson, Adams would resign from his ambassadorship and return to Massachusetts. During this time, he resumed his legal practice and became an outspoken critic of slavery. Three years later, he would be elected to the Senate. Although initially a supporter of the Federalist party (lead by Hamilton and his father), over the course of his tenure, Adams slowly began to align himself with the Jefferson-led Democratic-Republican party.

In 1807, after tensions with Britain began to rise, Jefferson proposed the “Embargo Act” in order to punish Britain for their actions. Adams broke party lines to support the bill, which caused the pro-British Federalists to deny him renomination, eventually forcing him to resign from his senate seat.

Adams’ support for Jefferson’s policies earned him favour with the Democratic-Republicans, eventually leading to Jefferson’s successor, James Madison, appointing Adams to the position of Ambassador to Russia in 1809 and eventually Ambassador to Great Britain in 1815. During this time, tensions between Britain and the U.S. escalated to the point of conflict, with the War of 1812 beginning while Adams was still in Russia. Madison put Adams in charge of negotiating a treaty to end the war, which he successfully did in 1814, securing an acceptable deal for the United States. His role in achieving peace landed him the position of Secretary of State under new President James Monroe, in charge of managing all of the government’s foreign relations, after Madison left office in 1817.

Secretary of State Adams

During his tenure as Secretary of State, Adams was responsible for drawing the Canada-United States border, negotiating new trade deals with European powers, pressuring Spain to give Florida to the U.S. (which he did successfully), afterwards writing and enacting the Monroe Doctrine, which was based upon the idea that the U.S. should take a more active role in foreign events. Simultaneously, Adams began to develop a new domestic policy. He began to believe that the government should take a more active role in developing the economy, ensuring success for its citizenry, and improving the nation’s infrastructure. These ideas came to be known as the “America System”, the idea that the government should take measures to improve the domestic affairs of the country. As strange as it may seem to us today, these ideas were incredibly controversial, as they conflicted with the long-standing Jeffersonian thought that the government should stay out of the economy and allow for private citizens to improve the country themselves. Despite his platform’s unpopularity, Adams would ultimately decide to run for President in the 1824 election, using his popularity to win the support of the majority northern Democratic-Republicans and former Federalists.

The Election of 1824

Initially, Adams chose General Andrew Jackson as his running mate, believing Jackson’s personal popularity among southerners would ease those worried about Adams’ anti-slavery views. However, Jackson later resigned from the ticket in order to run for President against Adams, fracturing the Democratic-Republican support between the two. Additionally, two other candidates ran, House Speaker Henry Clay and Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, both attracting support away from Adams.

On election day, no candidate would win, as none would receive the required number of votes. Jackson would come in first, with 99 electoral votes and 40.5 percent of the popular vote, while Adams placed second with 84 electoral votes and 32.7 percent of the popular vote. Crawford, with the support of the South, took 41 electoral votes and 11 percent of the popular vote, while Clay would take just 37 electoral votes and 13 percent of the popular vote. As per the rules set in the constitution, the House of Representatives would now decide the next President.

In February of 1825, the House met to decide the next President. With an endorsement from Clay, Adams would win on the first ballot, carrying 54.2 percent of the vote to Jackson’s 29.2. On March 4, 1825, he would be sworn in as the 6th President of the United States.

President Adams

Almost immediately, Adams sought to enact the America System, proposing the creation of a national university, expansion of the national bank, a new naval academy, a national astronomical observatory, greater support for scientific research and the arts, a new road to connect Washington, D.C. to New Orleans, Louisiana, and the creation of a “Department of the Interior” to manage land. Rather than raise taxes or take on debt, Adams devised a plan to fund these efforts by selling land to the west, simultaneously boosting the population, expanding the country, and developing the economy.

With the help of Clay, who Adams had appointed as his own Secretary of State, the new administration worked to write down a comprehensive series of legislation to propose over the first four years of Adams’ term. Additionally, Adams sought to re-write the government’s policies on Native Americans, favouring mutual agreements and gradual, consensual assimilation.

Unfortunately for Adams, the bitter, now-defeated Jackson had other plans. Although he lost the election, Jackson had won the popular vote, which upset the vast majority of his supporters. Additionally, Adams had largely won in the House thanks to the endorsement of Clay, who Adams had then appointed Secretary of State. Jackson began spreading rumours of a corrupt bargain, that Clay had given Adams the Presidency over him in exchange for an appointment to the cabinet. Using his influence, he was able to convince his supporters in Congress to block the America System. The astronomical observatory and national university never went to vote, the creation of the interior department was denied, and his new naval academy was blocked by the House.

In early 1828, Jackson would take this move a step further. With the help of his close ally Martin Van Buren, Jackson and his supporters separated from the Democratic-Republicans and created their own political party, known as the Democratic Party, or simply the Democrats for short. In response, Adams and Clay would form their own party, known as the National Republicans.

Part 2 of this article will cover the remainder of Adams’ story.

Sources: