The sun is beginning to peak from the horizon, filling the adamant blue sky with its orange hue. Around, morning dew leaves its mark on leaves, and the petrichor emanates from the grass, a reminder that a new season of life is yet to commence. For a moment, you are transfixed back into time, lost in the memories of your childhood. Drifting between the comfort and nostalgia from the lingering scent of the first rain and the softness of the grass, you find yourself amidst a distant memory. Transfixed, you lose sight of the present moment as you fall into a pleasant flashback and one that you may never experience again.

You may have gone through a moment such as this many times, as scents have the ability to suddenly trigger vivid memories in our brains. Moreover, our brains can associate life experiences with certain odours. These scents transport one back into time, bringing along with it a reflection of the moments that established an individual’s existence in the world.

Protuesian Moment

… I carried to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had let soften a bit of madeleine. But at the very instant when the mouthful of tea mixed with cake crumbs touched my palate, I quivered, attentive to the extraordinary thing that was happening inside me.

-Marcel Proust

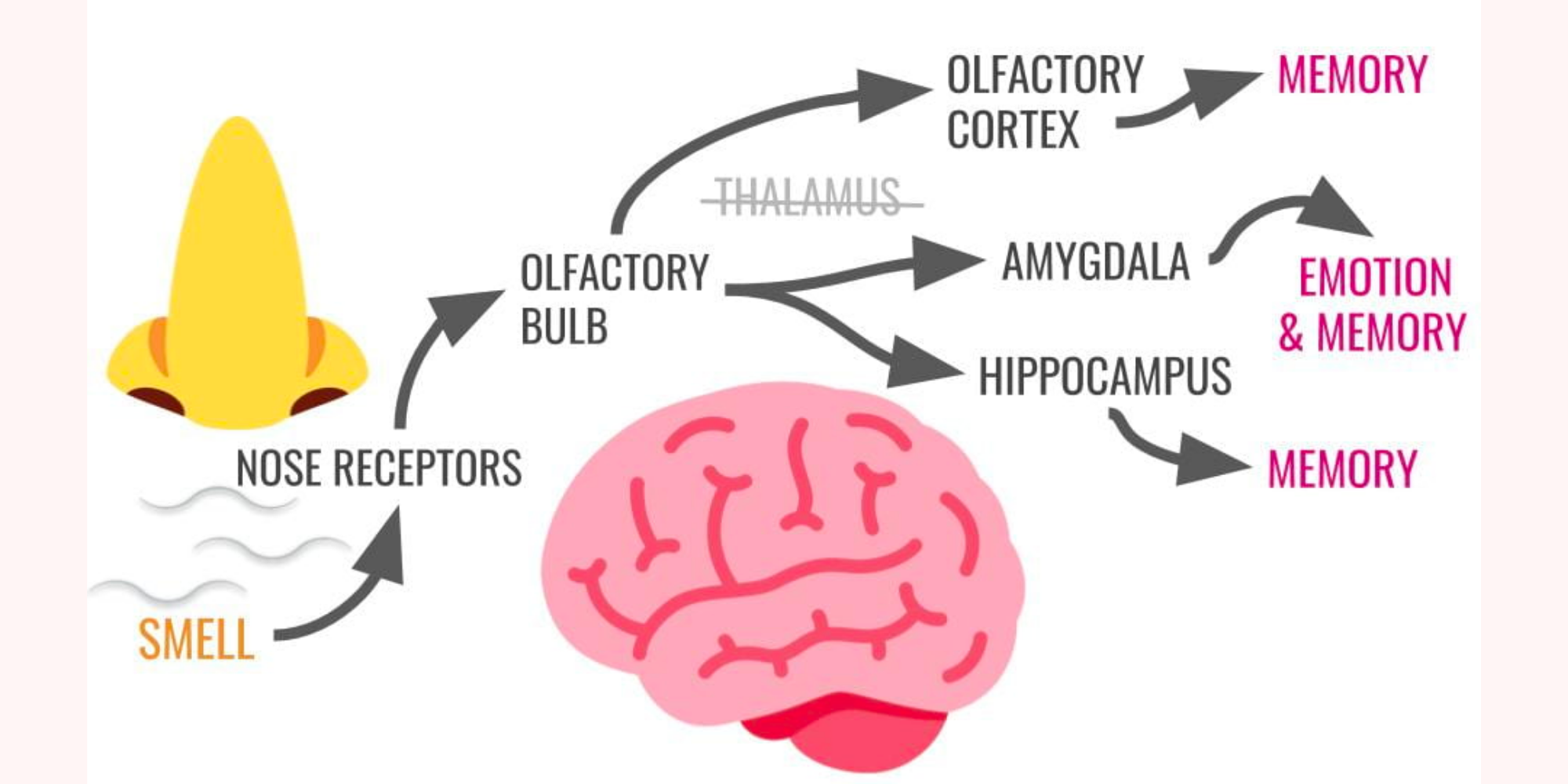

This interesting phenomenon has been categorized in literature as the Protuesian Moment, which comes from the excerpt above found in Marcel Proust’s “À la recherche du temps perdu.” It is used to describe a sensory experience that triggers a rush of memories that seem to be long forgotten. However, as surprising as this may seem, smell and memory are closely related to the brain’s anatomy, which makes this entirely plausible. More specifically, scents are up taken by the brain’s olfactory bulb. The olfactory bulb is a structure at the front of the brain that sends out information to the body’s central command for processing. Humans have around 400 types of different olfactory receipts, and our nervous systems categorise inputs from those receptors. This justifies the idea of why certain smells can only correlate to specific recollections that are otherwise forgotten in your daily life. Furthermore, odours also go to the limbic system, which includes the amygdala and hippocampus, which contribute to emotion and memory.

Scents and Brain Function

Flavours are another factor that an individual may associate with flashbacks into the past. On the contrary, those flavours are made tangible to the brain through smell, or rather one’s nose. When food is consumed, its particles reach the nasal epithelium. Thus, much of what your brain may process as “flavours” are actually aromas of certain ingredients in the food you are consuming. Additionally, our brains track the distinct smells we are subjected to in our daily lives. Sandeep Robert Dutta, a neuroscientist, and his team at Harvard Medical School have done a variety of tests that show the connection between smell and memory. His experiences suggest two main outcomes:

- Exposure to odours prompts smell-sensing cells to heighten the activity of genes that attenuated their responses to scents they were exposed to

- Memories from smells are coded in the brain

In the first outcome, when neurons pick up a scent, their sensitivity to the second decreases in that present moment. As a result, individuals become unaware of that certain scent when they are in a specific environment. In the second outcome, researchers witnessed how the brains of mice would change the location of where specific odours are mapped in the cortex when exposed to different smells at the same time.

A Deeper Dive into the Olfactory Bulb

It can be concluded that the olfactory receptors play a vital role in associating our senses with the brain. However, researchers in 2017 discovered that memories may be saved in the olfactory bulb itself, which is the piriform cortex. The piriform cortex connects to other sensory response regions in the brain. More specifically, this structure is called the orbitofrontal cortex, and its function is to make deductions about sensory inputs. Christina Strauch and Denise Manahan-Vaughan from Ruhr University Bochum used electrical impulses to stimulate this region, which consequently led to memory changes in the piriform cortex. The takeaway from this is that the piriform cortex can act as a long-term storage for memories, but it needs instruction from the orbitofrontal cortex. The orbitofrontal cortex indicates to the piriform cortex which memories need to be stored long-term.

Unfortunate Duality

Up until this point, memories triggered by scents were stated in a positive context. However, for some people, aromas can lead to past negative recollections or PTSD. War veterans are susceptible to this as fragrances of food can remind them of traumatic war zones. Some researchers suggest that other scents, such as coffee grounds or vanilla, can be used to counteract this emotional response. But, it should be noticed that this process would be subjective to each person. In recent research projects, scientists have also attempted to use the power of scent to aid people in recalling information. Advances in research studies such as this can lead to astounding new revelations in how smells can impact one’s test performances and memory processing abilities. More specifically, can associating scents with patterns or other images cause people to remember them more distinctly when compared to other traditional memorising techniques?

Image [1]

Featured image [1]