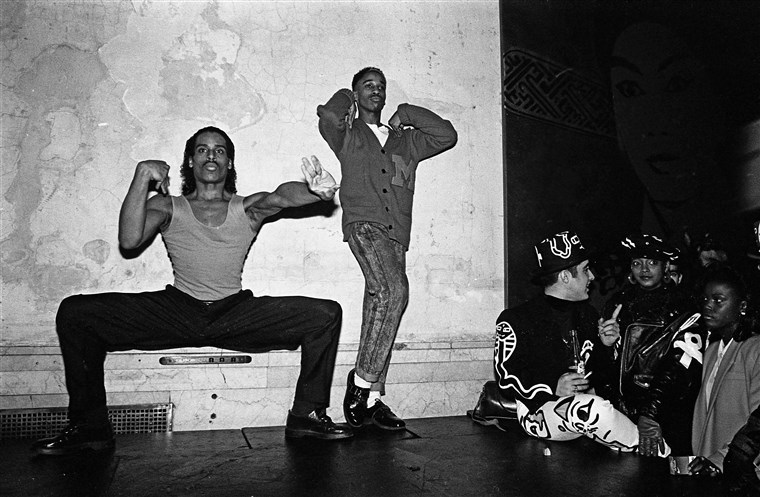

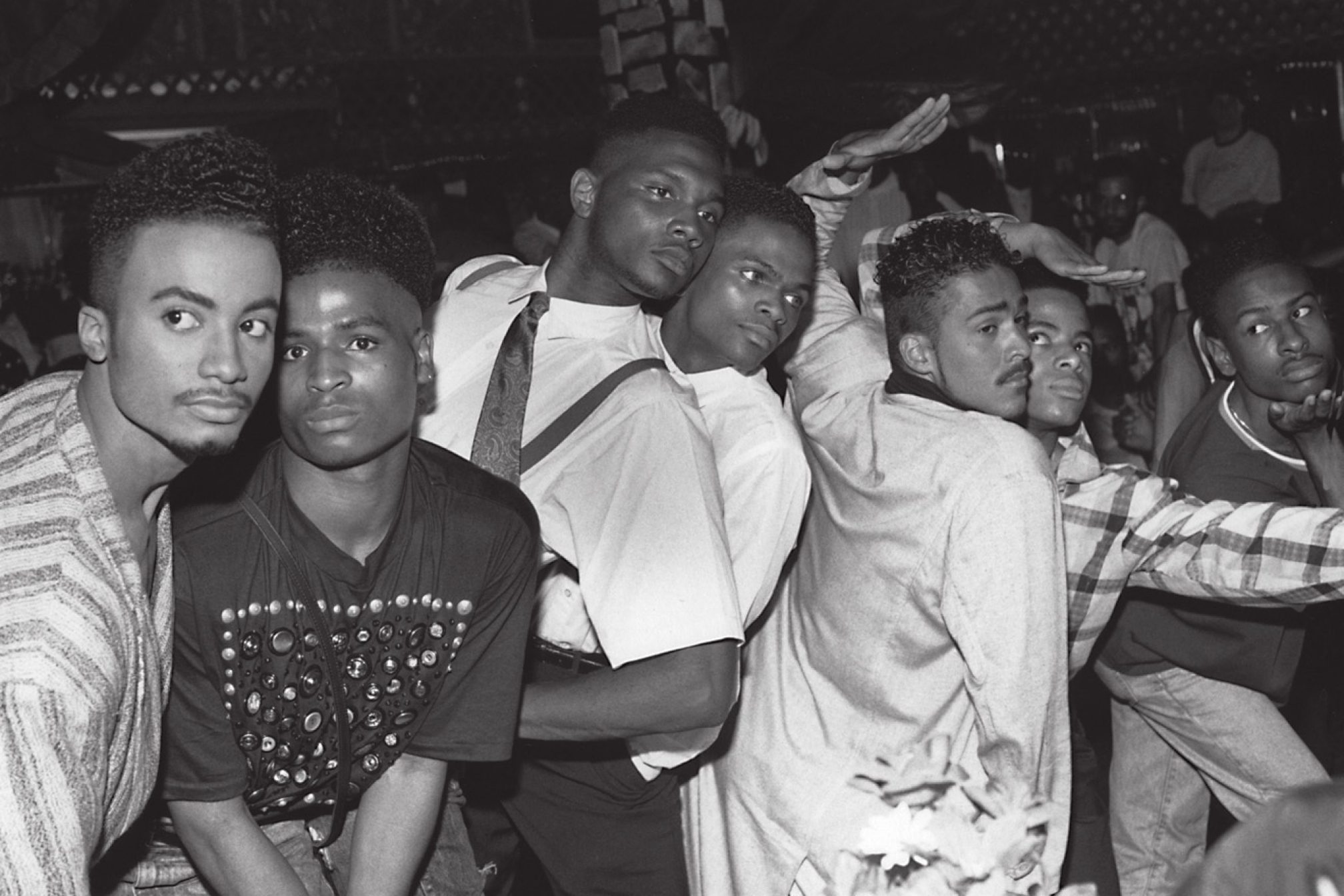

In 1980’s Harlem, the entirety of the queer community was hidden. In New York, the queer community survived in artful safe spaces of dance, creation, and expression. The drag ball scene is illuminated issues of race, gender, and sexual orientation faced by the marginalized communities of New York, and by extension, society as a whole. Ball culture emerged in the 1920s in New York City. The concept of balls is at its core, a means of self-expression for queer people. It involves drag, dance, and performance as a means of resisting societal norms, supporting queer expression, and simply, enjoying competition. At the beginning, performers at ball were primarily white men. People of colour began to establish their own ball community after the Stonewall Riots. When queer people of colour stood up to police, they

changed self-perceptions within the subculture: from feeling guilty and apologetic to feelings of self-acceptance and pride.

The 70s saw an expansion of ball participation as balls increased their numbers and categories to promote inclusivity. As a result, balls became a safe space for the deeply oppressed queer youth in New York, including black and Latinx queer kids. The world became aware of the existence of balls primarily through the cult classic, ‘Paris is Burning.’ The 1991 documentary is a time capsule of the ‘Golden Age’ of New York balls. The film followed the experience of gay people of colour, drag queens, and transgender women as they compete in fierce competition. The film alternates between the colourful ballroom to candid interviews addressing race, poverty, queer homelessness, class, gender orientation, and beauty standards. The film provides a profound deep dive into the survival tactics performed by New York’s devastatingly unique queer community. The documentary is also extremely quotable, introducing queer concepts of ‘shade.’ Much of this vocabulary is being retaught to society through shows such as RuPaul’s Drag Race, which take inspiration from ball culture. Although there has been concerns regarding the reduction of queer culture and people of colour in the film to a spectacle, the documentary did provide much needed representation for these ostracized communities. The film won Grand Jury Prize documentary at the Sundance Film Festival, among many other recognitions from critics and audiences. In 2016, it was added to the National Film Registry. The documentary did not receive any nominations at the Academy Awards, despite its glaring success and importance, leading to reform in the decisions making process at the Oscars.

‘Paris is Burning’ brought attention to the art and sport of voguing. The extremely expressive dance blends the boundaries of gender and identity in movements that uniquely communicates a desire for escape in sensual movement and uncontrollable energy. The ‘Grandfather of Vogue,’ Willi Ninja, rose to prominence within the Harlem Drag Ball scene in the 1980s. Ninja founded the ‘House of Ninja’ in 1982, acting as a ‘mother’ to adopted gay and transgender ‘children’ rejected by their communities and New York as a whole. Ninja provided a prominent support system and family that allowed for queer people to express themselves in gender-nonconforming presentations of dance an beauty.

Ninja helped shape the dance of voguing, which combined exaggerated model poses and intricate choreography. After his appearance in the documentary, Ninja rose to fame as a choreographer, musician, runway model, and modeling coach. Willi Ninja’s life provides insight into the intricacies of being black and gay in an inherently white and heteronormative world. He transgressed rigid gender barriers, committing to an androgynous gender presentation in dance and life. His intersectionality and talent led to the formation of a prominent legacy in the queer community and beyond. The House of Ninja keep voguing alive and advocate on behalf of Willi Ninja to raise awareness for HIV/AIDS and the discrimination faced by queer men with the disease.

Born William Roscoe Leake on April 12, 1961, Willi Ninja was a self-taught dancer. Not much is known about Ninja’s childhood, but in interviews he explained that his mother, Esther Leake, was accepting of his sexuality and had a prominent role in the nurturing his interest in dance. In an interview with Joan Rivers, Ninja described his acceptance from his mother, which was in contrast to the lives of the gay and transgender youth he mentored. Inspired by gymnasts and the martial arts, Willi Ninja formed a dance group called the ‘Video Pretenders,’ who would mimic dance scenes found on screen and in music videos from the 1980s. Ninja and his dance group began voguing with original choreography at the Christopher Street Pier and Washington State Park, popular site for queer youth, until he made his debut in Harlem’s drag balls. The culture originally surrounding drag balls and voguing can be traced back to the Harlem Renaissance (the Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual, social, and artistic explosion that took place in Harlem, New York, spanning the 1920s). Harlem’s Hamilton Lodge hosted its first queer masquerade in 1869. In newspapers, these balls were disguised as masquerades, but they came to be known as ‘fag balls’ or ‘parade of the fairies.’ During the Depression, Prohibition, and the criminalization of homosexual relations throughout the first half of the 20th century, the original Harlem scene experienced intense backlash and police intimidation. In the 1960s, the drag ball fragmented along racial lines, along with the intensification of the Civil Rights movement. When black queens attended balls, they were expected to ‘whiten up’ their faces if they wanted to win. Frustrations regarding racial bias led to events ran by black queens. In 1972, Crystal LaBeija formed the ‘House of LaBeija’ for a promotional gimmick for a drag ball. A drag daughter from the house, Pepper LaBeija, appears in ‘Paris is Burning.’ The formation of the house structure paralleled the increasingly prominent gay liberation movement and the reshaping of New York’s gangs. The house system provided an extended family that helped queer youth navigate the implications of racism, homophobia, transphobia, and class oppression. For far to many, these houses became the only family in their lives. The house system also makes a statement about the economic injustices in New York.

There was a decline in the city’s welfare and social services, early gentrification of urban neighbourhoods, decreases in funding for group homes and shelters for homeless youth, a sharp rise in unemployment rates among black and Latino men and a lack of funding during the Reagan era for people newly displaced or homeless as a result of HIV/AIDS. All these conditions forced black and gay (and especially black gay) people into the streets in unprecedented numbers, if they were not already disowned by their families for being gay or transgender.

Crystal LaBeija’s importance in the ball scene and to the survival of gay people of colour is still recognized today. Frank Ocean, a queer and black singer used Crystal LaBeija’s voice on his musical film, ‘Endless.’ In the interlude, ‘Ambience 001: In A Certain Way,’ Ocean samples a quote from LaBeija.

Because you’re beautiful and you’re young; you deserve to have the best in life.

The quote is taken from a 1968 documentary, ‘The Queen.’ Ocean also payed homage to the ball scene when he threw a ‘Paris is Burning’ themed birthday party.

The House of Ninja was known for its dancers. Queens competed in various categories to acquire trophies, placing their house higher in the drag ball hierarchy. The shift in the drag ball scene allowed the categories to be more inclusive, providing an ability to present singing and dancing as forms of expression. Willi Ninja participated in the scene to perfect his dance form, while others used it polish their modeling, singing, or other performance arts. Many of the queer youth could no obtain jobs or an education. As a result, categories involved the ‘children’ emulating executives, students, military men, runway models, and heterosexual men to allow them to present an identity they never get to experience in the outside world.

The balls were a reflection of a gender nonconforming group of queer people. These queens did not only attempt to imitate gender binaries. Ultimately, queens such as Ninja who did not ‘pass’ as a woman, attempted to break down institutionalized gender roles by dancing down the stage with a moustache, long hair, extravagant jewelry, make-up, women’s clothes, and a perfected blend on masculinity and femininity. Although many femme queens and transgender women found necessary validation in winning categories for their realness (ability to pass as a biological women), Willi Ninja, an androgynous, self-described butch queen, performed fluid gender presentation in a heteronormative world and a queer subculture that rewarded female realness. He simply wanted to showcase his abilities.

Voguing, in a similar fashion to hip-hop and break-dancing, emerged from black, poor, and working class communities as a form of expression, emphasizing male bonding. Paris DuPree, who also appeared in ‘Paris is Burning,’ created the style at the dance club ‘Footsteps.’ She was trying to out dance another queen when she grabbed a Vogue Magazine from her purse and began imitating the poses. Through throwing shade, DuPree invented a dance that remains popular. It is a contorted, sharp dance, combining model poses and pantomimic choreography. Willi Ninja redefined voguing by priding himself on being a clean, slicing dancer to,

kill his competition.

By adding swift, angular movements, and by including contortionist arm and leg positions, Ninja is credited for revolutionizing the dance form. Willi Ninja made voguing a legitimate dance form by teaching it all over the world. Ninja met musician Malcolm McLaren, who took a group headed by Willi on a tour of European fashion houses. Willi Ninja modeled in runway shows for Chanel, Jean Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler, Karl Lagerfield. Ninja taught voguing across Europe and Japan. He choreographed a appeared in various concerts and music videos. He took voguing to a new level of visibility and perfection. He trained models like Naomi Campbell and Iman, teaching female models femininity by showing them how to walk, grace, and poise. In 2004, Willi opened up EON (Elements of Ninja), a modeling agency.

In ‘Paris is Burning,’ Willi Ninja dreamed of travelling the world. After his success, he never lost touch with the ball scene. He was vital in getting the ballroom scene to discuss HIV/AIDS prevention throughout the 1980s when it was being ignored in the queer community because of the intense stigma and ignorance surrounding the issue. In 2003, Willi was diagnosed with HIV. He continued to support his elderly mother, while not being able to afford healthcare for himself. Willi Ninja continued to mentor upcoming dancers and models, until he lost his sight and became paralyzed. In New York City, Willi Ninja died of AIDS-related heart failure in 2006. At the age of 46, Willi passed surrounded by the children of his house. He continued to provide outlets for self-expression for queer youth. The House of Ninja continue to perform at drag balls to promote HIV/AIDS awareness.

Voguing is back. The legacy of Willi Ninja is living on in the queer kids of New York today. The Mugler Ball, which occurs in Queens, New York, invites new and legendary vogue dancers to compete on stage. These competitions have revealed that vogue ballroom culture has reached a new level of cultural influence. The critically adored fashion label, ‘Hood by Air,’ is founded by a former vogue dance, Shayne Oliver. The label frequently incorporates references to the dance on the runway. The New York Times recently speculated that Oliver may have had influence on the catwalks of Riccardo Tisci and Alexander Wang.

There’s a new generation exploring. There are more transsexuals, people are experimenting more,

said Joey Arias a drag performance artist.

The styles of the gender fluid queer ‘children’ in 1980’s Harlem was eclectic, but always well executed. Some queens even named their houses after fashion brands such as the ‘House of Balenciaga’ and the ‘House of St Laurent.’ Naming these vital family extensions after fashion brands was an intense act if devotion. However, today, ballroom culture seems to have a profound influence on fashion, art, music, and dance. The young queer kids of the balls are now the new arbiters of taste. Rashaad Newsome, a contemporary artist from New York, is arguably the godfather for the next generation of vogue. In 2010, Newsome released a voguing presentation on camera called ‘Untitled.’ The dancer in the project was a then-unknown Shayne Oliver.

Before [Untitled] I had never seen work in a gallery or institution about ballroom culture,

said Rashaad Newsome.

Newsome put on his own vogue extravaganza entitled ‘King of Arms Ball.’ He brought together influencers from the contemporary art and underground ballroom scene to watch dancing competitions. These modern balls are a celebration of gender fluidity, fashion, and beauty culture through the vessel of voguing. The impact of the 1980’s Harlem balls vibrantly displayed in the documentary, ‘Paris is Burning,’ has had a profound on contemporary arts. The brilliance and expression of legends like Willi Ninja has paved the way for societal acceptance of the LGBTQ community. There is still much room to improve in regards to diversity, but the queer community can look to the icons of balls to see that even in the face of marginalization, queer people and especially queer people of colour, will survive, thrive, and stare directly into the eyes of oppression and dance.

Ballroom and Voguing Images:

Sources-

Images-

Ballroom and Voguing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

A Note from the Author:

The history and art of balls and voguing is a profound example of human resilience. For me, it shows that even when society ostracizes people for visible differences, things like sexual orientation, or really anything that makes an individual different, that uniqueness doesn’t disappear, it just goes underground. The marginalized queer people of colour didn’t disappear from New York, they hid. That hiding allowed their identity to thrive and blossom into a unique form of expression and art. The self-expression that existed at these balls is truly beautiful. Ironically, something that was so hidden is now being revealed and used as inspiration in a world that is more accepting. Individuals like Willi Ninja are proof that no one should hide what they have. Ninja was not just a queer person of colour, he was also a talented dancer and personality that transcended any labels given to him. People portrayed in ‘Paris is Burning’ can serve as an inspiration to anyone. They show that there is no use diluting what you have, as it is truly beautiful and it will come out one way or another, even if it is underground.